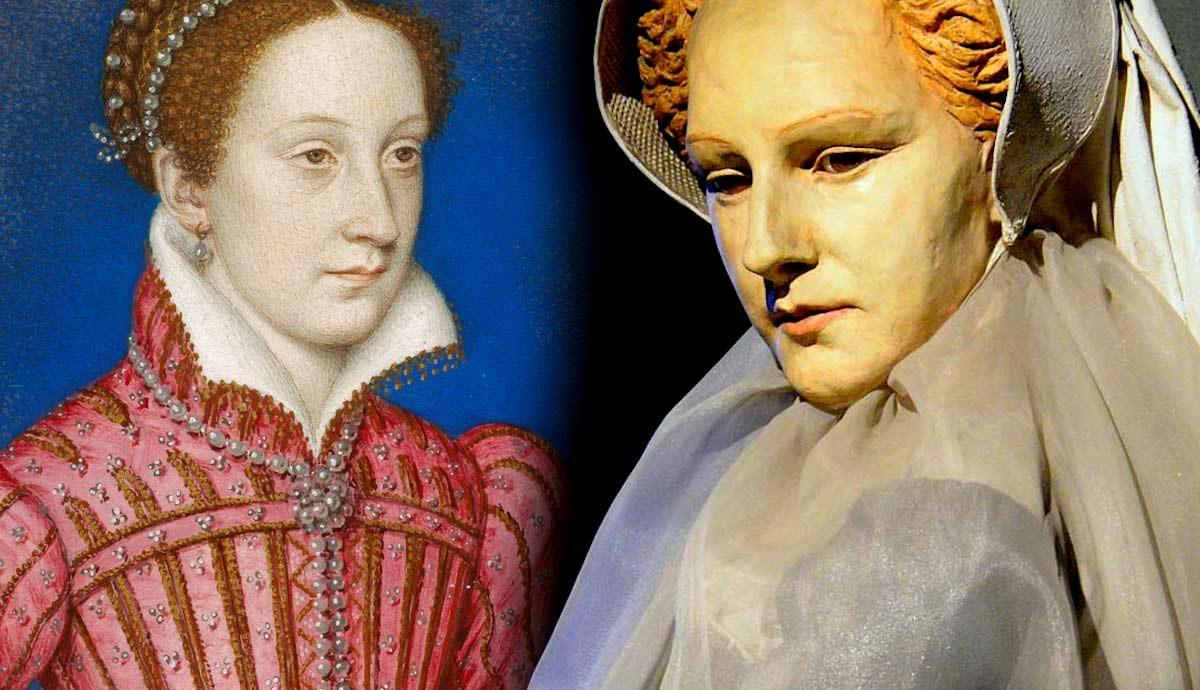

Mary, Queen of Scots, remains one of history’s most captivating and tragic figures. Born into royalty and destined for greatness, her life was marked by political intrigue, romance, betrayal, and eventual downfall. Her story intertwines with the turbulent history of 16th-century Scotland and England, leaving a legacy that continues to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts alike. This article delves into Mary’s dramatic rise to power and the events that led to her untimely fall.

Early Life and Ascension to the Throne

Mary Stuart was born on December 8, 1542, at Linlithgow Palace, Scotland, into the House of Stuart. Just six days later, her father, King James V, passed away, and the infant Mary was declared Queen of Scotland. The weight of the crown rested on her tiny head, but as an infant monarch, her rule was overseen by a series of regents who governed in her stead.

To strengthen Scotland’s alliance with France, Mary was betrothed to the Dauphin, Francis, at the tender age of five. In 1548, she was sent to the French court, where she spent her formative years. Surrounded by wealth, refinement, and the grandeur of Renaissance culture, Mary received an exceptional education, excelling in languages, music, and etiquette.

In 1558, at the age of 16, Mary married Francis, who ascended to the French throne a year later as King Francis II, making Mary both Queen of France and Queen of Scotland. Her time as Queen of France was brief, however; Francis died in 1560, leaving Mary widowed and without her French crown. With little choice, the young queen returned to her homeland, setting the stage for one of the most tumultuous reigns in Scottish history.

Return to Scotland and Political Turmoil

Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, a vastly different country from the one she had left. Scotland was divided by the Reformation, with Protestantism gaining ground against the Catholic faith. As a devout Catholic, Mary faced resistance from her Protestant subjects, including the fiery preacher John Knox, who openly criticized her rule.

In 1565, Mary married her cousin, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, in a union designed to strengthen her claim to the English throne. The marriage, however, quickly soured. Darnley was arrogant, power-hungry, and prone to jealousy. Tensions reached a boiling point in 1566 when Darnley, along with his co-conspirators, murdered Mary’s Italian secretary, David Rizzio, in her presence. This traumatic event severely damaged their relationship and Mary’s trust in her husband.

The Downfall: Scandal, Betrayal, and Imprisonment

In February 1567, Lord Darnley was found dead at Kirk o' Field under suspicious circumstances. His residence had been destroyed in an explosion, but Darnley’s body showed signs of strangulation, suggesting foul play. The prime suspect was James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, a close confidant of Mary.

Mary shocked the nation by marrying Bothwell just three months after Darnley’s death. This controversial union outraged the Scottish nobility, leading to a rebellion against her rule. Mary was forced to abdicate the throne in July 1567 in favor of her infant son, James VI of Scotland. She was imprisoned at Loch Leven Castle, from which she escaped in 1568, only to face defeat at the Battle of Langside. With her position in Scotland untenable, Mary fled to England, seeking the protection of her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I.

The Long Captivity

Mary’s arrival in England marked the beginning of 19 years of imprisonment. Though she was a guest in name, Mary was, in reality, a prisoner. As a Catholic queen with a legitimate claim to the English throne, she was a direct threat to Elizabeth’s Protestant rule.

Over the years, Mary became the focus of numerous Catholic plots to overthrow Elizabeth, including the infamous Babington Plot of 1586. While the extent of Mary’s involvement remains debated, intercepted letters linked her to the conspiracy, providing Elizabeth with the justification she needed to eliminate her rival.

The Execution of a Queen

On February 8, 1587, Mary, Queen of Scots, was executed at Fotheringhay Castle. Her death was a somber and dramatic affair, as she met her fate with dignity, draped in a crimson gown symbolizing Catholic martyrdom. Mary’s execution sent shockwaves across Europe and solidified her status as a tragic figure.

In a historical twist, her son, James VI of Scotland, eventually succeeded Elizabeth I as James I of England, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in 1603. This outcome, though far removed from Mary’s lifetime, highlighted the enduring significance of her bloodline.

Mary’s Enduring Legacy

Mary, Queen of Scots, continues to be a symbol of romance, resilience, and tragedy. Her life story has inspired countless works of literature, film, and art, portraying her as both a victim of circumstance and a flawed ruler. Landmarks such as Holyrood Palace, Linlithgow Palace, and Loch Leven Castle provide visitors with tangible connections to her legacy.

Mary’s life serves as a poignant reminder of the complexities of power, the dangers of political ambition, and the enduring allure of Scotland’s tumultuous history. Her story remains a cornerstone of Scottish heritage, evoking intrigue and sympathy centuries after her death.

Tags

Mary Queen of Scots, Scottish history, Tudor monarchy, Queen Elizabeth I, Linlithgow Palace, Holyrood Palace, James VI of Scotland, Scottish Reformation, Mary Stuart, Fotheringhay Castle